Brutal Burglary Or Murder By Madman? The Laurel Creek Murders

Were the 1909 Virginia murders a robbery or the work of a serial killer?

Late on the night of September 21, 1909, someone murdered six members of the Meadows family and set their log cabin on fire. The crime took place near Hurley, a tiny village in Buchanan County, VA, about 100 miles (160 km) south of Charleston, WV.

The tragic event has been referred to as the Meadows family murders, the Justus and Meadows family murders, or, more commonly, the Laurel Creek Murders.

Among the dead were George Meadows, his mother-in-law, Elizabeth “Aunt Betty” Justis, his wife, Lydia Meadows, and the couple’s three children, Will, Noah, and Lafayette, all under the age of 10. Each one had been struck in the head with an axe or hatchet.

We have this description of the scene from a letter from W. L. Dennis, former Buchanan County Clerk, which was published by the Roanoke World-News a week after the crime.

“It looked as if the head of Mrs. Justis had been cut off by an axe or hatchet and had been cut crosswise, laying some two or three feet from the body, and looked as though the head of one of the others had been cut off.

“(George) Meadows had been struck in the back of the neck with something like a hatchet and fell about thirty feet from the door. They shot him twice in the right side, about two inches apart.

“He had on his pants or overalls and one shoe, and one suspender on as if he had just been putting his clothes on. He had a pencil in his hand or near him as though he might have been trying to write down the names of those who committed the murder. If he did, it was burned up.”

Early on, officials and the press settled on robbery as the motive because Aunt Betty was known to keep a large sum of money in the home. Some sources suggested that she had $1,600 on hand (about $55,500 today).

Chasing the Hounds

Bloodhounds were brought to the scene and took up a trail the afternoon after the bodies were found. According to some reports, a posse of 300 armed men followed on the heels of the dogs. They were forced to stop at nightfall and resumed the chase at daybreak. At one point, they had to scale a head-high sheer cliff.

Finally, the hounds fetched up at the home of Silas Blankenship. Silas and his two sons were working in a cornfield when they saw the armed, angry mob descending on them. They quickly retreated to their cabin, grabbed shotguns, and made credible threats to blow the head off anyone who came too close.

The Blankenships were convinced to surrender and, at a preliminary hearing in Grundy, were able to provide a satisfactory alibi. An article in the next day’s Alexandria Gazette put forward the theory that the murderers might be foreigners from the coal fields.

The Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency was hired to solve the case. They arrested Howard Little, a local farmer, and former Ritter Lumber Company foreman. He had been convicted of murder in Kentucky and pardoned after serving four years, could not account for his whereabouts on the night of the murders, and had borrowed a .32-20 Smith & Wesson revolver from a friend days or weeks before the crime, depending on which account you go by.

George Meadows’ body was exhumed, and physicians recovered the two bullets. Based on their weight, they appeared to be .32 caliber. They did not conduct a microscopic comparison of the bullets. Ballistics matching would not be commonplace in the US for several more years, and the comparison microscope was not invented until 1925.

Questioning and trial did not go well for Little. A lantern was found in his barn, and multiple people testified that it belonged to Meadows. Little had a cut on his leg the day after the crime, which prosecutors suggested had happened the night of the murders and not the day after as Little claimed.

He was away from his house on the night in question, and no one provided an alibi for him. Although he was married and had four children, he had a married girlfriend, Mary Stacy. Not only would she not vouch for his whereabouts, but she also testified that they were planning to leave town as soon as he was able to withdraw some money out of his bank.

His wife made angry allegations but did not testify in court. At one point, she indicated to officers that she thought she knew where Little had hidden the money. However, the only money that was recovered was $900, which one of Mrs. Justis’ daughters found under the burned cabin’s sill.

Little did not take the stand in his own defense and instead relied on his lawyer to aggressively cross-examine witnesses. He was convicted on November 27 and executed in the electric chair on February 11, 1910. He went to his death calm and composed, denying any involvement in the murders to the last.

Forty days after the Meadows family was murdered and just over 100 days before Little was electrocuted for the crime, four members of the Hood family were murdered, and their house was set on fire about 80 miles from Hurley in Beckley, West Virginia.

The Tuesday, November 2, 1909, edition of the Fairmont West Virginian reported the deaths of Civil War Veteran George Hood, his son Roy Hood, his daughter Almeda Hood, and his granddaughter Emma Hood. George Hood’s skull had been crushed. Roy had been shot in the head. The bodies of Almeda and Emma were so badly burned that a cause of death could not be determined. The newspaper article ended with the following sentence:

“The crime, which is a repetition of the Grundy, Va., quadruple murder of a few weeks ago, has stirred the whole section of the state.”

An Unsettling Development

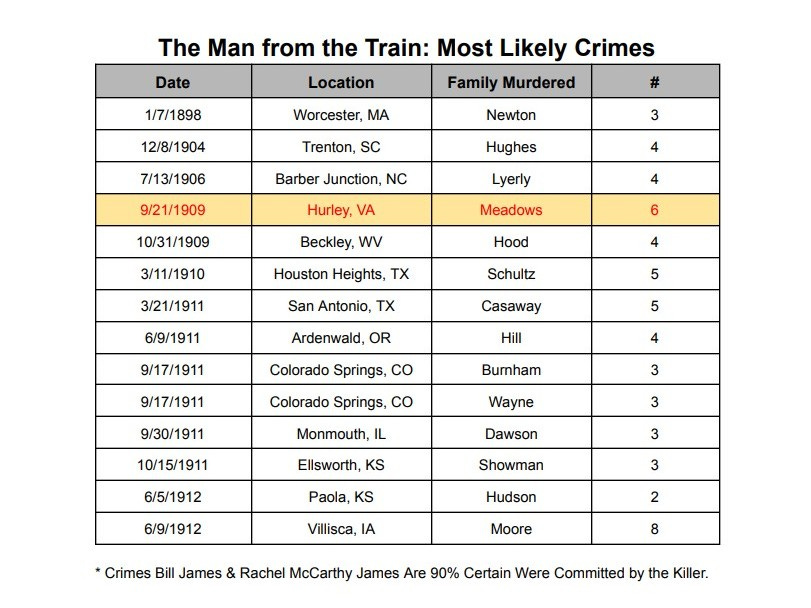

This brings us to The Man from the Train, a 2017 true crime book by Bill James and his daughter, Rachel McCarthy James. As you will recall from my last newsletter, the book explores the possibility of a serial killer traveling throughout the United States by train and murdering more than a dozen families from 1898 to 1912.

Bill James, in Chapter 35, “Hurley,” makes a strong case that the Meadows family murder is the work of this prolific serial killer. From the book:

“I absolutely believe that The Man from the Train committed this crime. It is too good a match for the other southern crimes for that not to be true, in my opinion, and also (b) the case against Howard Little seems to me to be flimsy, and (c) the case seems to be almost certainly connected to the murders of the Hood family, six weeks later and eighty miles away.”

Who killed the Meadows family? Howard Little or the Man from the Train? We will never know for certain. I’m putting my $5 down on the Man from the Train. Little was a dishonest man with a laundry list of character flaws, including a history of violence, but I don’t believe he had it in him to murder an entire family in cold blood with an ax.

Sources

James, Bill, and Rachel Mccarthy James. 2017. The Man from the Train: The Solving of a Century-Old Serial Killer Mystery. New York: Scribner.

Welton, Benjamin, and Jamie Frater. 2018. “10 Terrifying Facts about the Man from the Train.” Listverse. October 1, 2018. https://listverse.com/2018/10/01/10-terrifying-facts-about-the-man-from-the-train/.

Roanoke World-News, VA, Tuesday, September 28, 1909, Page 1, “A Gruesome Story of Buchanan Murder”

Alexandria Gazette, VA, Friday, September 24, 1909, Page 2, “Arrest of Suspects”

Richmond Times-Dispatch, VA, Sunday, October 03, 1909, Page 54, “Chain of Evidence Condemns Little”

Pittsburgh Press, PA, Saturday, November 27, 1909, Page 1, “Man Charged with Sextuple Murder Convicted by Jury”

Fairmont West Virginian, Tuesday, November 02, 1909, Page 6, “Hood Family was Murdered”

Raleigh Herald, Beckley, WV, Thursday, November 04, 1909, Page 1, “Horrible Crime Sunday Night”

Tazewell Republican, VA, Thursday, February 17, 1910, Page 1, “Howard Little Executed”